Why 'Turtles'?

Hindu teachings and meta-narratives… and also design?

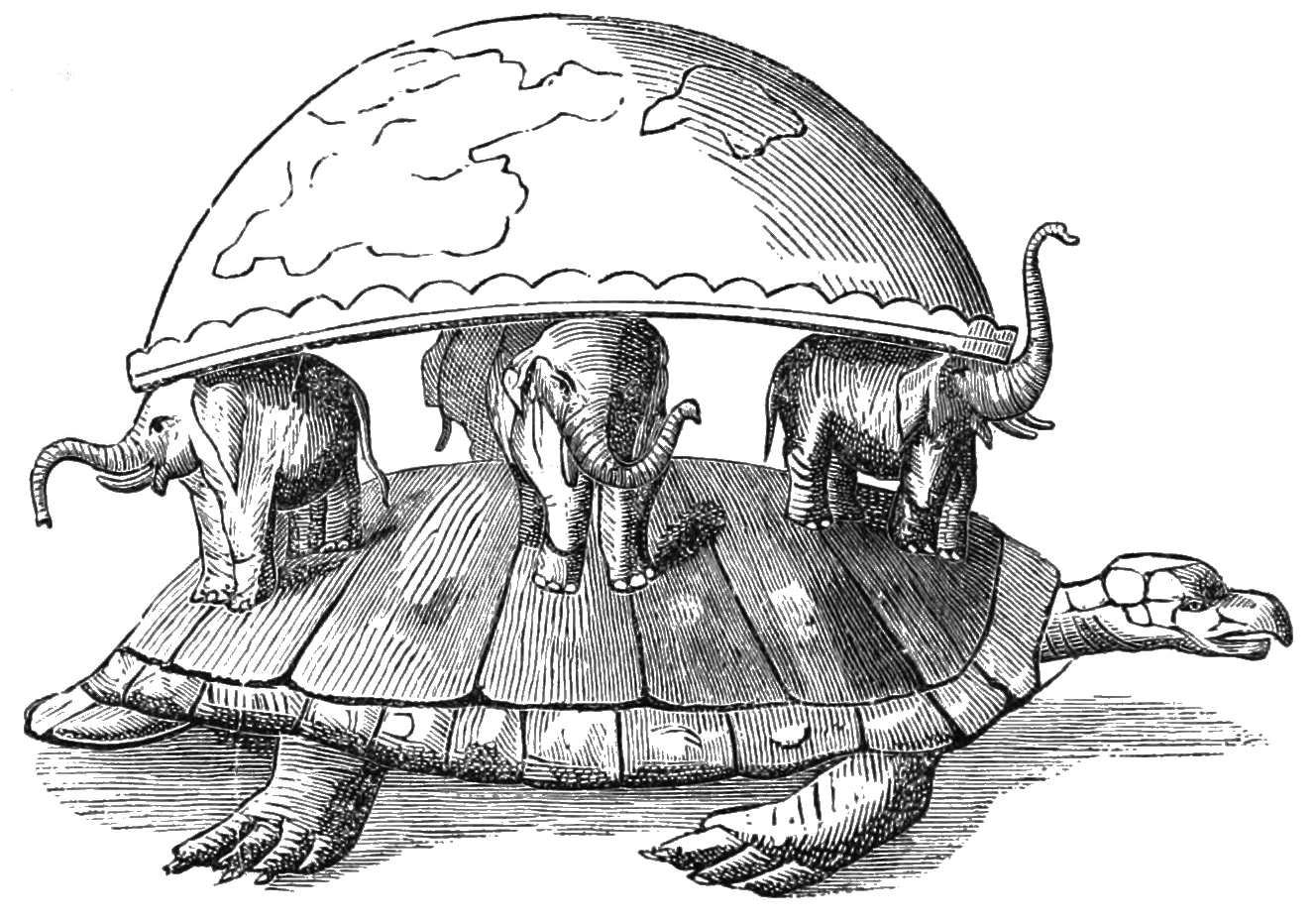

“It’s turtles all the way down.”

The saying is a fairly common one, and deals with a philosophical concept known as ‘infinite regress’. If the world is held up by four elephants, what holds up the elephants? If a turtle holds up the elephants, what holds up the turtle? “It’s turtles all the way down.” The ‘infinite regress’ in this example is the ‘origin’ of the earth: what causes the earth to exist?

Infinite regress occurs most frequently when dealing with causality:

“What caused this?”

“x caused this.”

“What caused x?”

“y caused x.”

Can you see the pattern? You could repeat this line of inquiry infinitely, and when we interrogate any causality of any kind we inevitably uncover the same problem. In essence, it is a gap in our ability to understand reality.

So, what to do? And what has it got to do with digital design?

Frameworks

A good friend of mine, who studies physics, told me recently that one of the primary functions of natural science is to create a ‘framework’ through which the evidence they have acquired about the physical world can make sense. From experimentation, you have a series of data sets, but they are meaningless without a structure with which to piece them together.

For example, we have sets of scientific laws for thermodynamics, evolution or the solar system, which have been compiled and widely agreed upon based on overwhelming evidence in their favour. However, few within scientific communities are under any illusion that these frameworks are perfect. Each contains gaps for which no one can find an answer. And, eventually, it is not uncommon for these frameworks to be replaced by a new framework at the discovery of particularly groundbreaking evidence. One example of this is the Copernican Revolution.

What piques my curiosity no end, is what does a different framework for understanding reality look like, where we are no longer faced with this issue of causality and infinite regress? If it isn’t turtles all the way down, what the hell is it?

A suitable place to start seems to be to ask what the framework currently is.

The Meta-Narrative

We live in a world (particularly the Western world) which is plagued by origin stories. Be it religions, nations, or since the industrial revolution, corporations.

Christianity teaches us that God created the Earth. Some (thankfully, few) British scholars teach us that the battle of three-hundred at Thermopylae during the Persian war was ‘the first English war’. Coca-Cola teaches us that Santa Claus has always worn the exact same shade of red as their brand.

These origin stories were given a name in 1979 by Jean-Francois Lyotard: ‘the grand meta-narrative’. (The Postmodern Condition, 1979)

Were you to read his work, you would quickly see that Lyotard was not a huge fan of these meta-narratives. His main reason for this are the inherent flaws that these stories deliberately hide in order to maintain their guise of ‘truth’.

Did God create the earth? At best, it is rather hard to prove. Was the battle of Thermopylae the first English war? It suggests a long, uninterrupted tradition of democratic rule extending from ancient Greece to modern-day Britain, which seems to brush over the thousand-plus years of autocracy that the country practiced (this is a great article on the topic). Has Santa always worn red? Actually, yes, thereabouts. Coca Cola did not, in fact, ‘rebrand’ Santa to their brand colours. However, they certainly did utilise their shared images to its full extent, and now it is second nature to imagine everyone’s favourite drink in the hand of the man who literally gives all children presents.

Why bother with these narratives?

As I explored in a previous article, it is for the pursuit of power. These narratives have allowed religions, nations and corporations to control their own image in such a manner that they cannot be questioned, and can inspire loyalty at will.

The Digital

Wasn’t I meant to be talking about design?

I believe that this framework of meta-narratives that constructs our framework for understanding reality permeates throughout design, particularly digital UI and UX design, which is chiefly concerned with the practice of disseminating information to large numbers of people.

We have digital environments that contains documents within folders, within folders, within folders. We have lists that scroll, further, further, further down. Is it just me, or does this sound a bit like my example of infinite regress?

It would appear, that as far as the world of digital design is concerned, it really is turtles all the way down.

But the digital space is only just beginning. And I am of the opinion we have only begun to scratch the surface of what can be accomplished with digital tools. If there was to be a technology that could offer a pathway to a new framework, which doesn’t fall at the question of causality, it is surely digital.

I named this newsletter ‘Turtles’ because I believe that this saying, which seeks to demonstrate the intrinsic issues with infinite regress, is one that needs to be heard more in the communities of digital design, and digital technology generally. I cannot promise answers to what a digital space that doesn’t succumb to turtles could be, but I intend to highlight where this framework permeates in digital design, and through analysis explain its limitations culturally, socially and philosophically.

I hope you will enjoy reading these articles, and they may help you to consider,

that it simply can’t be turtles all the way down.

Fascinating